Mayan Culture What Is the Meaning of Maya Art

Ancient Maya art is the visual arts of the Mayan civilization, an eastern and south-eastern Mesoamerican culture made upward of a slap-up number of small-scale kingdoms in nowadays-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize and Honduras. Many regional artistic traditions existed side by side, usually congruent with the changing boundaries of Maya polities. This civilisation took shape in the class of the later on Preclassic Period (from c. 750 BC to 100 BC), when the offset cities and monumental architecture started to develop and the hieroglyphic script came into being. Its greatest artistic flowering occurred during the vii centuries of the Archetype Catamenia (c. 250 to 950 CE).

Mayan art forms tend to be more stiffly organized during the Early on Archetype (250-550 CE) and to go more than expressive during the Late Archetype phase (550-950 CE). In the form of history, influences of various other Mesoamerican cultures were absorbed. In the late Preclassic, the influence of the Olmec style is still discernible (as in the San Bartolo murals), whereas in the Early on Classic, the style of cardinal Mexican Teotihuacan made itself felt, only every bit that of the Toltec in the Postclassic.

After the demise of the Archetype kingdoms of the central lowlands, ancient Maya art went through an extended Postclassic phase (950-1550 CE) centered on the Yucatan peninsula, before the upheavals of the sixteenth century destroyed courtly culture and put an end to the Mayan artistic tradition. Traditional fine art forms mainly survived in weaving and the design of peasant houses.

Maya art history [edit]

The nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century publications on Mayan fine art and archaeology by Stephens, Catherwood, Maudslay, Maler and Charnay for the get-go time made available reliable drawings and photographs of major Classic Maya monuments.

Studying a ruin at Izamal, Catherwood engraving

Following this initial stage, the 1913 publication of Herbert Spinden 'A Study of Maya Art' (now over a century ago ) laid the foundation for all later on developments of Maya art history (including iconography).[1] The book gives an analytical handling of themes and motifs, particularly the ubiquitous serpent and dragon motifs, and a review of the 'material arts', such equally the composition of temple facades, roof combs and mask panels. Spinden'due south chronological treatment of Maya art was later (1950) refined by the motif assay of the architect and specialist in archaeological drawing, Tatiana Proskouriakoff, in her volume 'A Study of Classic Maya Sculpture'.[2] Kubler'southward 1969 inventory of Maya iconography, containing a site-past-site handling of 'commemorative' images and a topical treatment of ritual and mythical images (such as the 'triadic sign'), concludes a period of gradual increase of knowledge that was soon to be overshadowed by new developments.

Starting in the early on 1970s, the historiography of the Mayan kingdoms – commencement of all Palenque – came to occupy the forefront. Art-historical estimation joined the historical arroyo pioneered past Proskouriakoff as well as the mythological approach initiated by M.D. Coe, with a professor of fine art, Linda Schele, serving as a driving force. Schele's seminal interpretations of Maya art are found throughout her work, especially in The Blood of Kings, written together with fine art historian M. Miller.[three] Mayan fine art history was also spurred past the enormous increment in sculptural and ceramic imagery, due to extensive archaeological excavations, likewise equally to organized looting on an unprecedented calibration. On from 1973, 1000.D. Coe published a series of books offer pictures and interpretations of unknown Maya vases, with the Popol Vuh Twin myth for an explanatory model.[4] In 1981, Robicsek and Hales added an inventory and classification of Mayan vases painted in codex style,[v] thereby revealing even more of a hitherto barely known spiritual earth.

As to subsequent developments, of import problems in Schele'southward iconographic work have been elaborated by Karl Taube.[half-dozen] New approaches to Maya fine art include studies of ancient Maya ceramic workshops,[7] the representation of bodily experience and the senses in Maya art,[eight] and of hieroglyphs considered as iconographic units.[9] Meanwhile, the number of monographs devoted to the monumental art of specific courts is growing.[10] A adept impression of recent Mexican and North American art historical scholarship can be gathered from the exhibition catalogue 'Courtly Art of the Ancient Maya' (2004).[xi]

Compages [edit]

Copan, 'Reviewing Stand' with simian musicians

Labna, Palace, vaulted passage

The layout of the Maya towns and cities, and more especially of the ceremonial centers where the royal families and courtiers resided, is characterized past the rhythm of immense horizontal stucco floors of plazas often located at diverse levels, continued by broad and often steep stairs, and surmounted past temple pyramids.[12] Nether successive reigns, the main buildings were enlarged by calculation new layers of fill and stucco coating. Irrigation channels, reservoirs, and drains made upwards the hydraulic infrastructure. Exterior the formalism middle (particularly in the southern area sometimes resembling an acropolis) were the structures of bottom nobles, smaller temples, and private shrines, surrounded past the wards of the commoners. Dam-like causeways (sacbeob) spread from the 'ceremonial centers' to other nuclei of dwelling house. Fitting in with the concept of a 'theatre state', more attention appears to have been given to aesthetics than to solidity of construction. Careful attention, withal, was placed on directional orientation.

Amid the various types of rock structures should be mentioned:

- Ceremonial platforms (usually less than four meters in height)

- Courtyards and palaces

- Other residential buildings, such as a writers' business firm [xiii] and a possible council business firm in Copan

- Temples and temple pyramids, the latter frequently containing burials and burying chambers in their base or fill, with sanctuaries on acme; outstanding example are the many amassed dynastic burial temples of Tikal Due north Acropolis

- Ball courts

- Sweat baths, particularly those of Piedras Negras and Xultun, the latter one with remains of stucco decoration.

Among the structural ensembles are:

- 'Triadic pyramids' consisting of a dominant structure flanked by ii smaller inwards-facing buildings, all mounted upon a single basal platform;

- 'East-groups' consisting of a foursquare platform with a low four-stepped pyramid on the west side and an elongated structure, or, alternatively, three small-scale structures, on the eastern side;

- 'Twin pyramid complexes', with identical four-stepped pyramids on the east and due west sides of a small plaza; a building with nine doorways on the south side; and a minor enclosure on the north side housing a sculpted stela with its altar and commemorating the king'south performance of a k'atun-ending anniversary.

In the palaces and temple rooms, the 'corbelled vault' was often practical. Though not an effective means to increase interior space, as it required thick stone walls to support the high ceiling, some temples utilized repeated arches, or a corbelled vault, to construct an inner sanctuary (eastward.g., that of the Temple of the Cantankerous at Palenque).

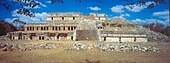

The northern Maya area (Campeche and Yucatan) shows characteristics of its own. Its Classic Puuc, Chenes, and Rio Bec architecture[14] is characterized past ornamentation in rock; geometrical reduction of realistic ornament; stacking of rain god snouts to build facades; apply of portals shaped similar serpent mouths; and, in the Rio Bec area, the use of solid pseudo temple-pyramids. The most important Puuc site is Uxmal. Chichen Itza, dominating Yucatán from the Belatedly Classic to well into the Mail service-Classic, features Archetype buildings in Chenes and Puuc fashion as well as Post-Classic building types of Mexican derivation, such every bit the radial four-staircase pyramid, the colonnaded hall, and the round temple. The latter features were inherited by the succeeding kingdom of Mayapan.

-

Chichen Itza, traditional Maya house

-

Palenque, Temple of the Inscriptions, Late Classic

-

Tikal Temple II, Tardily Archetype

-

Multistoried palace, Sayil, Yucatan, Late Archetype

-

Uxmal, Nunnery edifice, frieze with stacked pelting god snouts at corner, Late Archetype

-

Ball courtroom, Copan, Late Classic

Stone sculpture [edit]

Cancuen, console 3, seated rex with two subordinates. Second half 8th century.

Copan stela A, Maudslay cast

The main Preclassic sculptural style from the Maya area is that of Izapa, a large settlement on the Pacific coast where many stelas and (frog-shaped) altars were found showing motifs also present in Olmec art.[15] The stelas, more often than not without inscriptions, oftentimes show mythological and narrative subjects, some of which appear to chronicle to the Twin myth of the Popol Vuh. Yet, it remains uncertain if the inhabitants of Izapa were ethnically Mayan. For the Archetype Menstruum of the Mayas, the following major classes of stone sculpture, usually executed in limestone, may be distinguished.

- Stelas. These are large, elongated stone slabs normally covered with carvings and inscriptions, and frequently accompanied past round altars. Typical of the Classical period, most of them depict the rulers of the cities they were located in, frequently disguised every bit gods. Although the rulers' faces, particularly during the after Classic Period, are naturalistic in style, they commonly do not show private traits; but there are notable exceptions to this dominion (eastward.yard., Piedras Negras, stela 35). The nearly famous stelas are from Copan and nearby Quirigua. These are outstanding for their intricateness of detail, those of Quirigua also for sheer height (stela Due east measuring over seven metres above ground level and 3 below). Both the Copan and Tonina stelas approach sculptures in the round. From Palenque, otherwise a true Maya capital of the arts, no significant stelae have been preserved.

- Lintels, spanning doorways or jambs. Specially Yaxchilan is renowned for its long series of lintels in deep relief, some of the most famous of which bear witness meetings with ancestors or, perhaps, local deities.[sixteen]

- Panels and tablets, set in the walls and piers of buildings and the sides of platforms. This category is particularly well represented at Palenque, with the large tablets adorning the inner sanctuaries of the Cross Group temples, and with refined masterworks such as the 'Palace Tablet', the 'Tablet of the Slaves', and the multi-figure panels of the temple Nineteen and XXI platforms.[17] Male monarch Pakal's carved sarcophagus lid - without equal in other Maya kingdoms - might likewise be included hither.

- Relief columns flanking doorways in public buildings from the Puuc region (northwestern Yucatan) and similar in ornamentation to stelas.[18]

- Altars, rounded or rectangular, sometimes resting on three or four boulder-like legs. They may be wholly or partly figurative (e.thou., Copan turtle altar) or have a relief paradigm on top, sometimes consisting of a single Ahau twenty-four hour period sign (Caracol, Tonina).[nineteen]

- Zoomorphs, or big boulders sculpted to resemble supernatural creatures and covered with highly complicated relief ornamentation. These seem to be restricted to the kingdom of Quirigua during the Late Classic menstruation.[xx]

- Ball court markers, or relief roundels placed in the central axis of the floors of ball courts (such as those of Copan, Chinkultic, Tonina), and usually showing royal ball game scenes.

- Monumental stairs, well-nigh famously the behemothic hieroglyphic stairway of Copan. The hewn stone blocks of hieroglyphic stairways together establish an extensive text. Stairways can besides be decorated with a not bad variety of scenes (La Corona), particularly the ball game. Sometimes, the ball game becomes the stairs' chief theme (Yaxchilan), with a captive depicted within the ball, or, elsewhere (Tonina), a full-figure captive stretched out along the step.

- Thrones and benches, the thrones with a broad, square seat, and a back sometimes iconically shaped like the wall of a cave and worked open to show man figures. Benches, covered with relief on the forepart, tend to be incorporated into the surrounding architecture; they are more than elongated, and lack a back support. Examples from Palenque and Copan take supports showing cosmological carriers (Bacabs, Chaaks).

- Stone sculpture in the round is especially known from Copan and Toniná. Information technology is represented by bronze, such as a seated Copan scribe as well as convict figures and small stelas from Toniná; by certain figurative architectural elements, such as the twenty maize deities from the façade of Copan Temple 22;[21] and past giant sculptures such as the symmetrically-positioned jaguars and simian musicians of Copán, that were integral parts of architectural pattern.

-

Piedras Negras throne 1, with heads restored, Late Classic (Museo Nacional de Antropología east Historia de Guatemala)

-

Tonina monument 151, bound prisoner, Classic

Wood carving [edit]

It is believed that carvings in wood were one time extremely common, but merely a few examples have survived. Most 16th-century wood carvings, considered objects of idolatry, were destroyed by the Spanish colonial authorities. The most important Classic examples consist of intricately worked lintels, generally from the main Tikal pyramid sanctuaries,[22] with 1 specimen from nearby El Zotz. The Tikal wood reliefs, each consisting of several beams, and dating to the 8th century, evidence a king on his seat with a protector effigy looming big behind, in the form of a Teotihuacan-mode 'state of war snake' (Temple I lintel two), a jaguar (Temple I lintel 3), or a homo impersonator of the jaguar god of terrestrial burn (Temple IV lintel 2). Other Tikal lintels depict an obese male monarch wearing a jaguar clothes and standing in front of his seat (Temple Iii lintel 2); and nearly famously, a victorious king, dressed as an astral expiry god, and standing on a palanquin underneath an arching feathered snake (Temple Iv lintel three). A rare utility object is a tiny lidded box from Tortuguero with hieroglyphic text all around it. Gratis sculpture in wood, dating dorsum to the 6th century, is represented past a dignified seated man possibly functioning every bit a mirror bearer.

Stucco modeling [edit]

Stucco mask panels, Early Classic, Kohunlich

At least since Tardily Preclassic times, modeled and painted stucco plaster covered the floors and buildings of the town centers and provided the setting for their stone sculptures. Often, large mask panels with the plastered heads of deities in high relief (particularly those of lord's day, rain, and earth) are found fastened to the sloping retaining walls of temple platforms flanking stairs (eastward.thou., Kohunlich). Stucco modeling and relief piece of work can likewise encompass the entire edifice, as shown by Temple 16 of Copan, in its 6th-century form (known equally 'Rosalila'). Dedicated to the first king, Yax K'uk' Mo', this early temple has preserved plastered and painted facades. The stuccoed friezes, walls, piers, and roof combs of the Late Preclassic and Classic periods show varying and sometimes symbolically complicated decorative programs.

Several solutions for dividing upward and ordering the stuccoed surfaces of buildings were practical, serialization being one of them. The Early Archetype walls of the 'Temple of the Dark Dominicus' in El Zotz consist of a serial of subtly varied deity mask panels, whereas the frieze of a Balamku palace, also from the Early Classic, originally had a series of 4 rulers enthroned above the open up ophidian mouths of four dissimilar animals (a toad among them) associated with symbolic mountains. Conversely, friezes may be centered on a single ruler again sitting on a symbolic (maize) mountain, such as a frieze from Holmul, with two feathered serpents emanating from below the ruler's seat, and some other one from Xultun, on which the ruler carries a large ceremonial bar with emerging jaguar-similar figures.[23] An Early-Archetype temple frieze from Placeres, Quintana Roo, has the large mask console of a young lord or deity in the centre, with two lateral 'Grandfather' deities extending their artillery.

Often, a frieze is divided into compartments. Late Preclassic friezes of El Mirador, for example, show the intervening spaces of an undulating serpent's body filled out with aquatic birds, and the sections of an aquatic band with swimming figures.[24] Similarly, a Classic palace frieze in Acanceh is divided into panels belongings dissimilar beast figures[25] reminiscent of wayob, while a wall in Tonina has lozenge-shaped fields suggesting a scaffold and presenting continuous narrative scenes that relate to human sacrifice.[26]

Plastered roof combs are similar to some of the friezes in a higher place in that they normally show large representations of rulers, who may over again be seated on a symbolic mountain, and also, as on Palenque'southward Temple of the Sun, set within a cosmological framework. Further examples of Classic stucco modeling include the piers of the Palenque Palace, embellished with a series of lords and ladies in ritual dress, and the 'baroque', Belatedly-Classic Chenes-manner stucco entrance, aggress with naturalistic human figures, on the Acropolis (Str. 1) of Ek' Balam.

Unique in Mesoamerica, Classic Menstruum stucco modeling includes realistic portraiture of a quality equalling that of Roman ancestral portraits, with the lofty stucco heads of Palenque rulers and portraits of dignitaries from Tonina equally outstanding examples. The modeling recalls that of certain Jaina ceramic statuettes. Some, but not all, of these portrait heads were one time office of life-size stucco figures adorning temple crests.[27] In the same way, 1 finds stucco glyphs that were one time a office of stuccoed texts.

-

Balamku, part of a frieze, toad seated on mount icon and belging forth king, Archetype

-

Palenque Palace, Firm D, item of stucco relief showing h2o lilies, long-nosed deity head and legs of seated figure, Archetype

-

Palenque Templo Olvidado, calendrical glyphs detached from stucco text on pillar, Classic

-

Hormiguero, stucco head ("Maya Akhenaten"), Late Classic (Museo arqueológico Fuerte de Due south. Miguel, Campeche)

Landscape painting [edit]

Bonampak mural, room 1, east wall: Musicians

San Bartolo mural: The rex equally Hunahpu

Although, due to the humid climate of Central America, relatively few Mayan paintings accept survived to the present twenty-four hours integrally, of import remnants have been found in nearly all major court residences. This is peculiarly the case in substructures, hidden nether later architectural additions. Mural paintings may prove more or less repetitive motifs, such equally the subtly varied flower symbols on walls of Firm Due east of the Palenque Palace; scenes of daily life, as in one of the buildings surrounding the primal foursquare of Calakmul and in a palace of Chilonche; or ritual scenes involving deities, equally in the Post-Classic temple murals of Yucatán'south and Belize's east coast (Tancah, Tulum, Santa Rita).[28] The latter murals betray a potent influence of the so-called 'Mixteca-Puebla way' once widely spread beyond Mesoamerica.

Murals may also evince a more narrative character, normally with hieroglyphic captions present. The colourful Bonampak murals, for example, dating from 790 Ad, and extending over the walls and vaults of iii adjacent rooms, bear witness spectacular scenes of nobility, battle and sacrifice, also as a group of ritual impersonators in the midst of a file of musicians.[29] At San Bartolo, murals dating from 100 BCE chronicle to the myths of the Maya maize god and the hero twin Hunahpu, and depict a double inthronization; antedating the Classic Period by several centuries, the style is already fully developed, with colours being subtle and muted every bit compared to those of Bonampak or Calakmul.[30] Outside the Mayan area, in a ward of East-Key Mexican Cacaxtla, murals painted in a predominantly Archetype Mayan mode, with frequently stark colors, have been establish, such as a savage boxing scene extending over 20 meters; two figures of Mayan lords continuing on serpents; and an irrigated maize and cacao field visited by the Maya merchant deity.[31]

Wall painting also occurs on vault capstones, in tombs (e.one thousand., Río Azul), and in caves (due east.g., Naj Tunich),[32] ordinarily executed in blackness on a whitened surface, at times with the additional employ of red paint. Yucatec vault capstones oft show a delineation of the enthroned lightning deity (e.chiliad., Ek' Balam).

A bright turquoise bluish color - 'Maya Blue' - has survived through the centuries due to its unique chemic characteristics; this colour is present in Bonampak, Cacaxtla, Jaina, El Tajín, and fifty-fifty in some Colonial Convents. The use of Maya Bluish survived until the 16th century, when the technique was lost.[33]

Writing and bookmaking [edit]

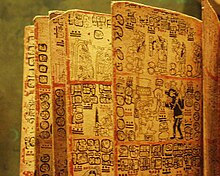

The Maya writing system consists of about thou distinct characters or hieroglyphs ('glyphs'), and like many ancient writing systems is a mixture of syllabic signs and logograms. This script was in use from the 3rd century BCE until shortly after the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. As of at present (2021), a considerable proportion of the characters has a reading, but their pregnant and configuration as a text is not always understood. The books were folded and consisted of bark paper or leather leaves with an adhesive stucco layer on which to write; they were protected past jaguar peel covers and, perhaps, wooden boards.[34] Since every augur probably needed a book, there must accept existed large numbers of them.

Today, three Mayan hieroglyphic books, all from the Postal service-Classic period, are still in existence: the Dresden, Paris, and Madrid codices. A quaternary book, the Grolier, is Maya-Toltec rather than Maya and lacks hieroglyphic texts; fragmentary and of very poor workmanship, information technology shows many anomalies, reason for which its actuality has long remained in doubt.[35] These books are largely of a divinatory and priestly nature, containing almanacs, astrological tables, and ritual programs; the Paris Codex also includes katun-prophecies. Great attending was paid to a harmonious balance of texts and (partly coloured) illustrations.

Besides the codical glyphs, there existed a cursive script of an oftentimes dynamic graphic symbol, found in wall-paintings and on ceramics, and imitated in stone on panels from Palenque (such as the 'Tablet of the 96 glyphs'). Oft, written captions are enclosed in square 'boxes' of various shapes inside the representation. Wall paintings may likewise entirely consist of texts (Ek' Balam, Naj Tunich), or, more than rarely, comprise astrological computations (Xultun); sometimes, written on a white stuccoed surface, and executed with detail intendance and elegance, these texts are like enlargements of book pages.

Hieroglyphs are ubiquitous and were written on every bachelor surface, including the homo body. The glyphs themselves are highly detailed, and particularly the logograms are deceivingly realistic. As a matter of fact, from an art-historical betoken of view, they should as well be viewed as art motifs, and vice versa.[9] Sculptors at Copan and Quirigua have consequently felt gratis to catechumen hieroglyphic elements and calendrical signs into animated, dramatic miniature scenes ('full figure glyphs').[36]

Ceramics and 'ceramic codex' [edit]

Codex style cylinder vessel, courtly ritual

Unlike utility ceramics found in such large numbers among the debris of archaeological sites, most of the busy pottery (cylinder vessels, lidded dishes, tripod plates, vases, bowls) in one case was 'social currency' among the Maya nobility, and, preserved as heirlooms, also accompanied the nobles into their graves.[37] The aristocratic tradition of gift-giving feasts[38] and ceremonial visits, and the emulation that inevitably went with these exchanges, goes a long way towards explaining the high level of artistry reached in Classical times.

Made without a potter'southward wheel, busy pottery was delicately painted, carved into relief, incised, or - chiefly during the Early Archetype catamenia - made with the Teotihuacan fresco technique of applying pigment to a wet clay surface. The precious objects were manufactured in numerous workshops distributed over the Mayan kingdoms, some of the most famous existence associated with the 'Chama-style', the 'Holmul-manner', the so-called 'Ik-style'[39] and, for carved pottery, the 'Chochola-style.'[40]

Vase ornamentation shows keen variation, including palace scenes, courtly ritual, mythology, divinatory glyphs, and even dynastical texts taken from chronicles, and plays a major role in reconstructing Classical Maya life and beliefs. Ceramic scenes and texts painted in blackness and ruby on a white underground, the equivalents of pages from the lost folding books, are referred to as being in 'Codex Way' (due east.yard., the so-called Princeton Vase). The hieroglyphical and pictural overlap with the 3 extant books is (at least upwards to now) relatively small.

Sculptural ceramic art includes the lids of Early Classic bowls mounted by human being or brute figures; some of these bowls, burnished blackness, are among the nearly distinguished Mayan works of art ever created.

Ceramic sculpture as well includes incense burners and burial urns. All-time known are the profusely decorated Classic burners from the kingdom of Palenque, which take the modeled face of a deity or of a rex attached to an elongated hollow tube. The deity most often depicted, the jaguar deity of terrestrial burn down, as well adorns large Archetype burying urns from the Guatemalan section of El Quiché.[41] The elaborate Post-Classic, mold-made effigy incense burners specially associated with Mayapan represent continuing deities (or priestly deity impersonators) ofttimes carrying offerings.[42]

Finally, figurines, often mold-fabricated, and of an amazing liveliness and realism, constitute a pocket-sized but highly informative genre. Apart from deities, animal persons, rulers and dwarfs, they show many other characters besides every bit scenes taken from daily life.[43] Some of these figurines are ocarinas and may have been used in rituals. The most impressive examples stalk from Jaina Island.

-

Codex-style vase with mythological scene, 7th–8th century (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Vessel with throne scene, Chamá style, late seventh–eighth century (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Relief vase with head of aquatic serpent, Chocholá way, Yucatan, Late Classic (Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin)

-

Lidded basal flange bowl, El Peru, Republic of guatemala, Early Classic (Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología de Guatemala)

-

Tripod bowl with heron chapeau, Early Classic (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Lower part of incense burner, Palenque style, Late Archetype (Walters Art Museum)

-

Urn with jaguar deity lid, Late Archetype (Walters Art Museum)

-

Costumed effigy, 7th–8th century (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Immature nobleman as a flower, Jaina style, eighth century (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Precious rock and other sculpted materials [edit]

Marble belt aggregation with celt pendants, from the tomb of king Pakal, Palenque

Jade plaque from Nebaj, showing king flanked past 'Pax trees' with maize leafage

Information technology is remarkable that the Maya, who had no metal tools, created many objects from a very thick and dumbo cloth, jade (jadeite), peculiarly all sorts of (royal) clothes elements, such as belt plaques - or celts - ear spools, pendants, and also masks. Celts (i.east., apartment, celt-shaped ornaments) were sometimes engraved with a stela-like representation of the king (eastward.yard., the Early on-Classic 'Leyden Plate'). The best-known example of a mask is probably the death mask of the Palenque king Pakal, covered with irregularly-shaped marble plaques and having eyes made from mother-of-pearl and obsidian; some other death mask, belonging to a Palenque queen, consists of malachite plaques. Similarly, certain cylindrical vases from Tikal have an outer layer of foursquare jade discs. Many stone carvings had jade inlays.

Among other sculpted and engraved materials are flint, chert, beat out, and os, often found in caches and burials. The so-called 'eccentric flints' are ceremonial objects of uncertain use, in their most elaborate forms of elongated shape with normally various heads extending on 1 or both sides, sometimes those of the lightning deity, but more often of an anthropomorphic lightning probably representing the Tonsured Maize God.[44] Trounce was worked into disks and other decorative elements showing human, perchance ancestral heads and deities; conch trumpets were similarly busy.[45] Man and creature bones were decorated with incised symbols and scenes. A collection of small and modified, tubular bones from an 8th-century royal burying nether Tikal Temple I contains some of the most subtle engravings known from the Maya, including several scenes with the Tonsured maize god in a canoe.[46]

-

Jadeite deity confront pendant, seventh–8th century (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Jadeite rain deity with arms in royal posture, Early on Classic (Metropolitan Museum of Fine art)

-

Jade chugalug plaque with ruler, Early Classic (Kimbell Art Museum)

-

Funerary mask of a Palenque queen covered with pieces of malachite, 7th century (site museum)

Applied arts and body ornamentation [edit]

Textiles from the Classic period, made of cotton wool, accept not survived, but Maya fine art provides detailed data virtually their appearance and, to a lesser extent, their social office.[47] They include delicate fabrics used every bit wrappings, curtains and canopies furnishing palaces, and garments. Amongst the dyeing techniques may have been ikat. Daily costume depended on social standing. Noblewomen normally wore long dresses, noblemen girdles and breechcloths, leaving legs and upper body more or less bare, unless jackets or mantles were worn. Both men and women could wear turbans. Costumes worn on ceremonial occasions and during the many festivities were highly expressive and exuberant; animate being headdresses were mutual. The well-nigh elaborate costume was the formal apparel of the king, equally depicted on the royal stelae, with numerous elements of symbolic meaning.[48]

Wickerwork, only known from incidental depictions in sculptural and ceramic art,[49] must once have been ubiquitous; the well-known popular ('mat') motif testifies to its importance.[50]

Trunk decorations often consisted of painted patterns on face and body, but could also exist of a permanent character marker status and age differences. The latter blazon included artificial deformation of the skull, filing and incrustation of the teeth, and tattooing of the face.[51]

Museum collections [edit]

There are a peachy many museums across the world with Maya artifacts in their collections. The Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies lists over 250 museums in its Maya Museum database,[52] and the European Association of Mayanists lists only under 50 museums in Europe alone.[53]

In Mexico City, the Museo Nacional de Antropología contains an peculiarly large selection of Maya artifacts.[54] A number of regional museums in United mexican states hold important collections, including Museo Amparo in Puebla, with its famous throne back from Chiapas; the Museo de las Estelas "Román Piña Chan" in Campeche;[55] the Museo Regional de Yucatán "Palacio Cantón" in Mérida; and the Museo Regional de Antropología "Carlos Pellicer Camera" in Villahermosa, Tabasco.[56]

In Guatemala, the most important museum collections are those of the Museo Popol Vuh and the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, both in Guatemala City,[54] with many smaller pieces on display in the "El Príncipe Maya" museum, Cobán. In Belize, Maya artefacts can be found in the Museum of Belize and the Bliss Institute; in Honduras, in the Copan Sculpture Museum and in the Galería Nacional de Arte, Tegucigalpa.

In the The states, almost every major art museum has a collection of Maya artifacts, often including stone monuments. Amongst the more important e coast collections are those of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Princeton University Art Museum; the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology in Cambridge, Massachusetts; the Dumbarton Oaks collection;[57] and the Academy of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeology and Anthropology, with its famous countdown stela 14 of Piedras Negras. On the west coast, the De Young Museum of San Francisco and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, with its large drove of painted Maya ceramics, are important. Other notable collections include the Cleveland Museum of Art in Ohio, the Fine art Institute of Chicago, and the Chicago Field Museum of Natural History, which contains a selection of Maya ceramics excavated by J. Eric S. Thompson.

In Europe, the British Museum in London exhibits a series of famous Yaxchilan lintels, and the Museum der Kulturen in Basel, Switzerland, a number of wooden lintels from Tikal. The Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin holds a broad selection of Maya artifacts, including an incised Early on-Classic vase showing a king lying in state and awaiting post-mortem transformation. The Museo de América in Madrid hosts the Madrid Codex likewise equally a large selection of artifacts from Palenque.[56] Other notable European museums are the Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde in Leiden, Netherlands, domicile to La Pasadita lintel 2 and the Leyden Plate; the Musées royaux d'fine art et d'histoire in Brussels;[55] and the Rietberg Museum in Zürich, Switzerland.[56]

Maya performative arts [edit]

- Maya dance

- Maya trip the light fantastic drama

- Maya music

Run across also [edit]

- Ancient Maya graffiti

- Pre-Columbian art

- Painting in the Americas before Colonization

- Visual arts by ethnic peoples of the Americas

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ Spinden 1975

- ^ Proskouriakoff 1950

- ^ Schele and Miller 1986

- ^ Code 1973, 1975, 1978, 1982

- ^ Robicsek and Hales 1981

- ^ Due east.g., Miller and Taube 1993; Taube et al. 2010

- ^ Reents-Budet 1994

- ^ Houston et al. 2005

- ^ a b Stone and Zender 2011

- ^ Tate 1992, Looper 2003, Simmons Clancy 2009, O'Neil 2012

- ^ Miller and Martin 2004

- ^ Stierlin 1994

- ^ Coe and Kerr 1997: 100-101

- ^ Gendrop 1983

- ^ Guernsey 2006

- ^ Tate 1992

- ^ Stuart and Stuart 2008

- ^ Mayer 1981

- ^ Martin and Grube 2000: 89

- ^ Looper 2003: 172-178, 186-192

- ^ Schwerin 2011

- ^ West.R. Coe et al. 1961

- ^ newmedia.ufm.edu/gsm/alphabetize.php/Saturnoxultun

- ^ Doyle and Houston 2012

- ^ V.E. Miller 1991

- ^ see Yadeun 1993:108-115

- ^ Martin and Grube 2000: 168

- ^ Miller 1982; Gann 1900

- ^ M.Eastward. Miller 1986; M.Eastward. Miller and Brittenham 2013

- ^ Saturno et al. 2005; Taube et al. 2010

- ^ Lozoff Brittenham and Uriarte 2015

- ^ Rock 1995

- ^ Reyes-Valerio 1993; Houston et al. 2009

- ^ Coe and Kerr 1997

- ^ Love 2017

- ^ Houston 2014: 108-117

- ^ Reents-Budet 1994: 72ff

- ^ Tozzer 1941: 92

- ^ Just 2012

- ^ Tate 1985

- ^ McCampbell 2010

- ^ Thompson 1957; Milbrath 2007

- ^ Halperin 2014

- ^ Agurcia, Sheets, Taube 2016

- ^ Finamore and Houston 2010: 124-131

- ^ Trik 1963

- ^ Looper 2000

- ^ E.g., Dillon and Christensen 2005

- ^ Reents-Budet 1994: 331

- ^ Robicsek 1975

- ^ Houston et al. 2006: 18-25

- ^ Ros.

- ^ "Museums & Collections - Wayeb". wayeb.org.

- ^ a b Wagner 2011, p. 451.

- ^ a b Wagner 2011, p. 450.

- ^ a b c Wagner 2011, p. 452.

- ^ Pillsbury et al. 2012

References [edit]

- Agurcia Fasquelle, Ricardo, Payson Sheets, and Karl Andreas Taube (2016). Protecting Sacred Space. Rosalila's Eccentric Chert Cache at Copan and Eccentrics among the Archetype Maya. Monograph 2. San Francisco: Precolumbia Mesoweb Press.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Coe, Michael D., The Maya Scribe and His World. New York: The Grolier Club 1973.

- Coe, Michael D., Classic Maya Pottery from Dumbarton Oaks. Washington: Trustees of Harvard University 1975.

- Coe, Michael D., Lords of the Underworld; Masterpieces of Archetype Maya Ceramics. New Bailiwick of jersey: Princeton Academy Press 1978.

- Coe, Michael D., One-time Gods and Young Heroes; The Pearlman Drove of Maya Ceramics. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum 1982.

- Coe, Michael D., and Justin Kerr, The Art of the Maya Scribe. Thames and Hudson 1997.

- Coe, William R., Edwin K. Shook, and Linton Satterthwaite, 'The Carved Wooden Lintels of Tikal'. Tikal Report No. half-dozen, Tikal Reports Numbers 5-x, Museum Monographs, The University Museum, U. of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia 1961.

- Dillon, Brian D., and Wes Christensen, 'The Maya Jade Skull Bead: 700 Years every bit Military Insignia?'. In Brian D. Dillon and Matthew A. Boxt, Archaeology without Limits. Papers in Honor of Cloudless W. Meighan, pp. 369–388. Lancaster: Labyrinthos 2005.

- Doyle, James, and Stephen Houston, 'A Watery Tableau at El Mirador, Guatemala'. In Maya Decipherment, Apr ix, 2012 (decipherment.wordpress.com.).

- Finamore, Daniel, and Stephen D. Houston, The Peppery Puddle: The Maya and the Mythic Ocean. Peabody Essex Museum 2010.

- Gann, Thomas, Mounds in Northern Republic of honduras. 19th Annual Report, Smithsonian Institution, Washington 1900.

- Gendrop, Paul, Los estilos Río Bec, Chenes y Puuc en la arquitectura maya. Mexico: UNAM (División de Estudios de Posgrado, Facultad de Arquitectura) 1983.

- Guernsey, Julia, Ritual and Ability in Rock: The Performance of Rulership in Mesoamerican Izapan Style Fine art. Austin: University of Texas Press 2006.

- Halperin, Christina T., Maya Figurines. Intersections between Land and Household. University of Texas Press 2014.

- Houston, Stephen, The Life Within. Classic Maya and the Affair of Permanence. New Haven and London: Yale University Press 2014.

- Houston, Stephen, et al., The Memory of Bones. Torso, Being, and Experience among the Archetype Maya. Austin: U. of Texas Press 2006.

- Houston, Stephen, et al., Veiled Effulgence. A History of Aboriginal Maya Color. Austin: U.of Texas Press 2009.

- Merely, Bryan R., Dancing into Dreams. Maya Vase Painting of the Ik' Kingdom. Yale University Press 2012.

- Kubler, George, Studies in Classic Maya Iconography. Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences, 28. New Haven: Connecticut 1969.

- Looper, Matthew, Gifts of the Moon: Huipil Designs of the Aboriginal Maya. San Diego Museum Papers 38. San Diego: San Diego Museum of Human, 2000.

- Looper, Mathhew, Lightning Warrior. Maya Fine art and Kingship at Quirigua. Austin: U. of Texas Printing 2003.

- Love, Bruce, 'Authenticity of the Grolier Codex remains in dubiousness'. Mexicon Vol. XXXIX Nr. 4 (2017): 88-95.

- Lozoff Brittenham, Claudia, and María Teresa Uriarte, The Murals of Cacaxtla: The Ability of Painting in Ancient Central Mexico. Austin: U. of Texas Press 2015.

- Martin, Simon, and Nicolas Grube, Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens. Thames&Hudson 2000.

- Maudslay, A.P., Biologia Centrali-Americana. Text and 4 Vols. of Illustrations. London 1889-1902.*

- Mayer, Karl Herbert, Classic Maya Relief Columns. Acoma Books, Ramona, California 1981.

- McCampbell, Kathleen K., Highland Maya Effigy Funerary Urns. A Report of Genre, Iconography, and Function. MA Thesis, Florida State Academy 2010 (online).

- Milbrath, Susan, Mayapán'south Figure Censers: Iconography, Context, and External Connections. www.famsi.org/reports (2007)

- Miller, Arthur G., On the Edge of the Bounding main. Mural Painting at Tancah-Tulum, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks 1982.

- Miller, G.E., 'The History of the Report of Maya Vase Painting'. In Maya Vase Book Vol. 1, ed. J. Kerr, New York: 128-145.

- Miller, M.E., and Megan O'Neil, Maya Art and Architecture. New York and London: Thames and Hudson 2014.

- Miller, M.E., The Murals of Bonampak. Princeton U.P. 1986.

- Miller, K.E., and Claudia Brittenham, The Spectacle of the Late Maya Courtroom. Reflections on the Murals of Bonampak. Austin: Texas U.P. 2013

- Miller, Mary, and Simon Martin, Courtly Art of the Aboriginal Maya. Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. Thames and Hudson 2004.

- Miller, Mary, and Karl Taube, The Gods and Symbols of Aboriginal Mexico and the Maya. An Illustrated Lexicon of Mesoamerican Organized religion. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Miller, Virginia E., The Frieze of the Palace of the Stuccoes, Acanceh, Yucatan, Mexico. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art & Archaeology, 39. Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks 1991.

- O'Neil, Megan, Engaging Ancient Maya Sculpture at Piedras Negras, Guatemala. Norman: U. of Oklahoma Press 2012.

- Pillsbury, Joanne, et al., Ancient Maya Art at Dumbarton Oaks. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2012.

- Proskouriakoff, Tatiana, A Study of Classic Maya Sculpture. Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication No. 593, 1950

- Reents-Budet, Doreen, Painting the Maya Universe: Majestic Ceramics of the Archetype Period. Duke U.P. 1994.

- Reyes-Valerio, Constantino, De Bonampak al Templo Mayor, Historia del Azul Maya en Mesoamerica. Siglo XXI Editores, 1993.

- Robicsek, Francis, A study in Maya art and history : the mat symbol. New York: Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, 1975.

- Robicsek, Francis, and Donald Hales, The Maya Book of the Dead: The Corpus of Codex Style Ceramics of the Late Classic period. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 1981.

- Ros, Narin. "Maya Museum Database". Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies. Archived from the original on 2014-07-08. Retrieved 2015-06-08 . Full listing from FAMSI archived from the original on 2015-06-08.

- Saturno, William; David Stuart and Karl Taube (2005). The Murals of San Bartolo, El Petén, Republic of guatemala, Part I: The North Wall. Ancient America 7.

- Schele, Linda, and Mary Ellen Miller, The Blood of Kings. Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. New York: George Braziller, Inc., in association with the Kimbell Art Museum.

- Schwerin, Jennifer von, 'The sacred mount in social context. Symbolism and history in Maya Architecture: Temple 22 at Copan, Honduras.' Aboriginal Mesoamerica 22(2), September 2011: 271-300.

- Simmons Clancy, Flora, The Monuments of Piedras Negras, an Aboriginal Maya City. Albuquerque: U. of New Mexico Press 2009.

- Spinden, Herbert, A Study of Maya Art: Its Field of study Matter & Historical Development. New York: Dover Publ., 1975.

- Stierlin, Henri, Living Architecture: Mayan. Architecture of the World, 10. Benedikt Taschen Verlag, 1994.

- Stone, Andrea J., Images from the Underworld. Naj Tunich and the Tradition of Maya Cave Painting. 1995. ISBN 978-0-292-75552-nine

- Stone, Andrea, and Marc Zender, Reading Maya Fine art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting and Sculpture. Thames and Hudson 2011.

- Stuart, David, and George Stuart, Palenque, Eternal City of the Maya. Thames and Hudson 2008.

- Tate, Carolyn East., The Carved Ceramics Called Chochola. In fifth Palenque Round Table, PARI, San Francisco 1985: 122-133.

- Tate, Carolyn E., Yaxchilan: The Design of a Maya Ceremonial Urban center. Austin: U. of Texas Printing 1992.

- Taube, Karl; David Stuart, William Saturno and Heather Hurst (2010). The Murals of San Bartolo, El Petén, Guatemala, Role two: The West Wall. Aboriginal America x.

- Thompson, J.E.S., Deities portrayed on censers at Mayapan. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Electric current Reports, No. forty (July 1957).

- Tozzer, Alfred M., Landa's Relación de las cosas de Yucatán. A Translation. Peabody Museum, Cambridge MA 1941.

- Trik, Aubrey S., 'The First-class Tomb of Temple I At Tikal, Republic of guatemala'. Trek (Fall 1963): three-18.

- Wagner, Elisabeth (2011) [2006]. "Una Selección de Colecciones y Museos". In Nikolai Grube (ed.). Los Mayas: Una Civilización Milenaria (in Spanish). Potsdam, Federal republic of germany: Tandem Verlag GmbH. pp. 450–452. ISBN978-3-8331-6293-0. OCLC 828120761.

- WAYEB. "Museums & Collections". European Association of Mayanists (WAYEB). Archived from the original on 2015-05-11. Retrieved 2015-06-08 .

- Wren, Linnea, et al., eds. Landscapes of the Itza: Archeology and Art History at Chichen Itza and Neighboring Sites. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 2018.

- Yadeun, Juan, Toniná. Mexico: El Equilibrista / Madrid: Turner Libros 1993.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maya art. |

- Maya art, National Museum of the American Indian

- Azulmaya:Maya Blue Pigment

- 'Authentic Maya'

- Kerr Maya Vase Data Base & Precolumbian Portfolio

- UNAM: Ancient Prehispanic Murals

dobsonalienighted.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Maya_art

0 Response to "Mayan Culture What Is the Meaning of Maya Art"

Post a Comment